Art History

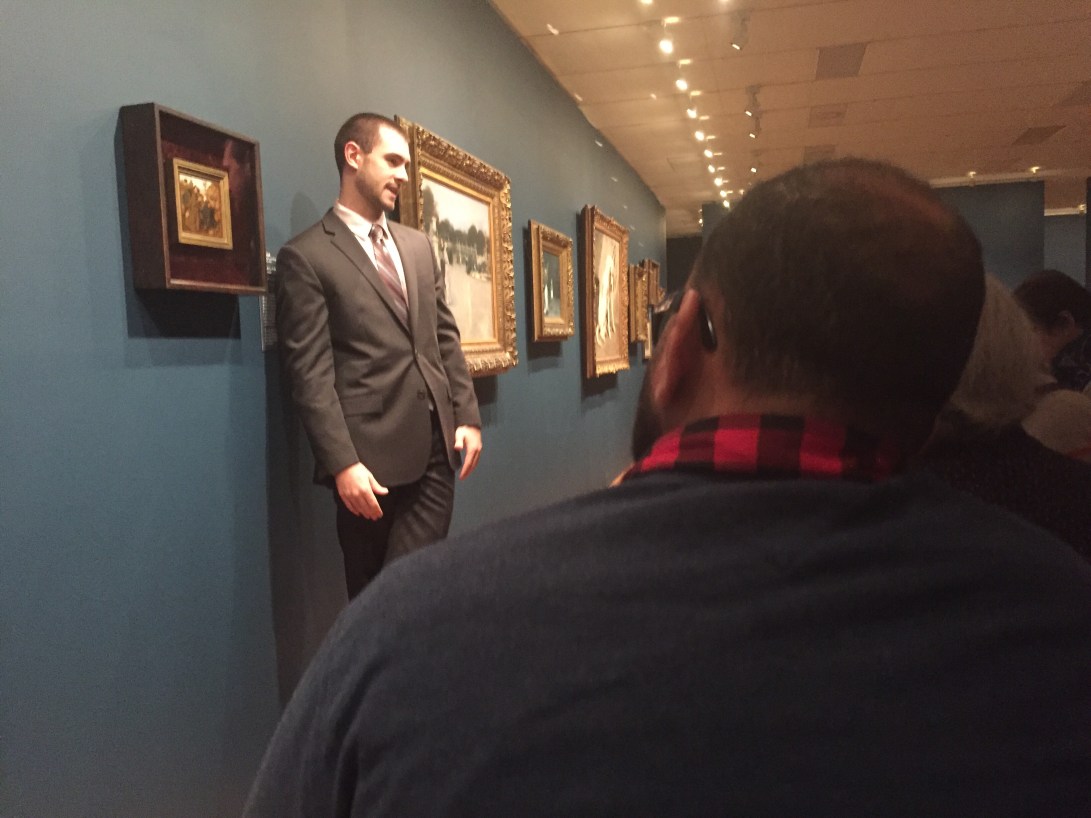

Remarks on, Joaquín Torres-García: The Arcadian Modern – Museum of Modern Art 02/01/16

The MoMA’s new exhibit, Joaquín Torres-García: The Arcadian Modern, is a compelling and accessible installation. Joaquín’s story is a fascinating one. As a young man, he was exposed to the avant-garde art movement in Europe. Later in his career, he would travel back to his home country of Uruguay. Today in South America, his work is still celebrated and he’s considered a national hero. I feel that the exhibit put a particular emphasis on the importance of style. The exhibit uses Joaquín’s work to form a generalization of each artist search for their signature style. As Joaquín was growing into himself, he was experimenting with many different styles and techniques. As you will see, his works vary significantly over his career. Even though this exhibit is meant to focus on Joaquín’s Arcadian works, I feel that it better portrays his story of self discovery. Joaquín Torres-García: The Arcadian Modern takes the audience inside the mind of a true innovator and pioneer. A man who can proudly claim responsibility for evolving art into what it is today.

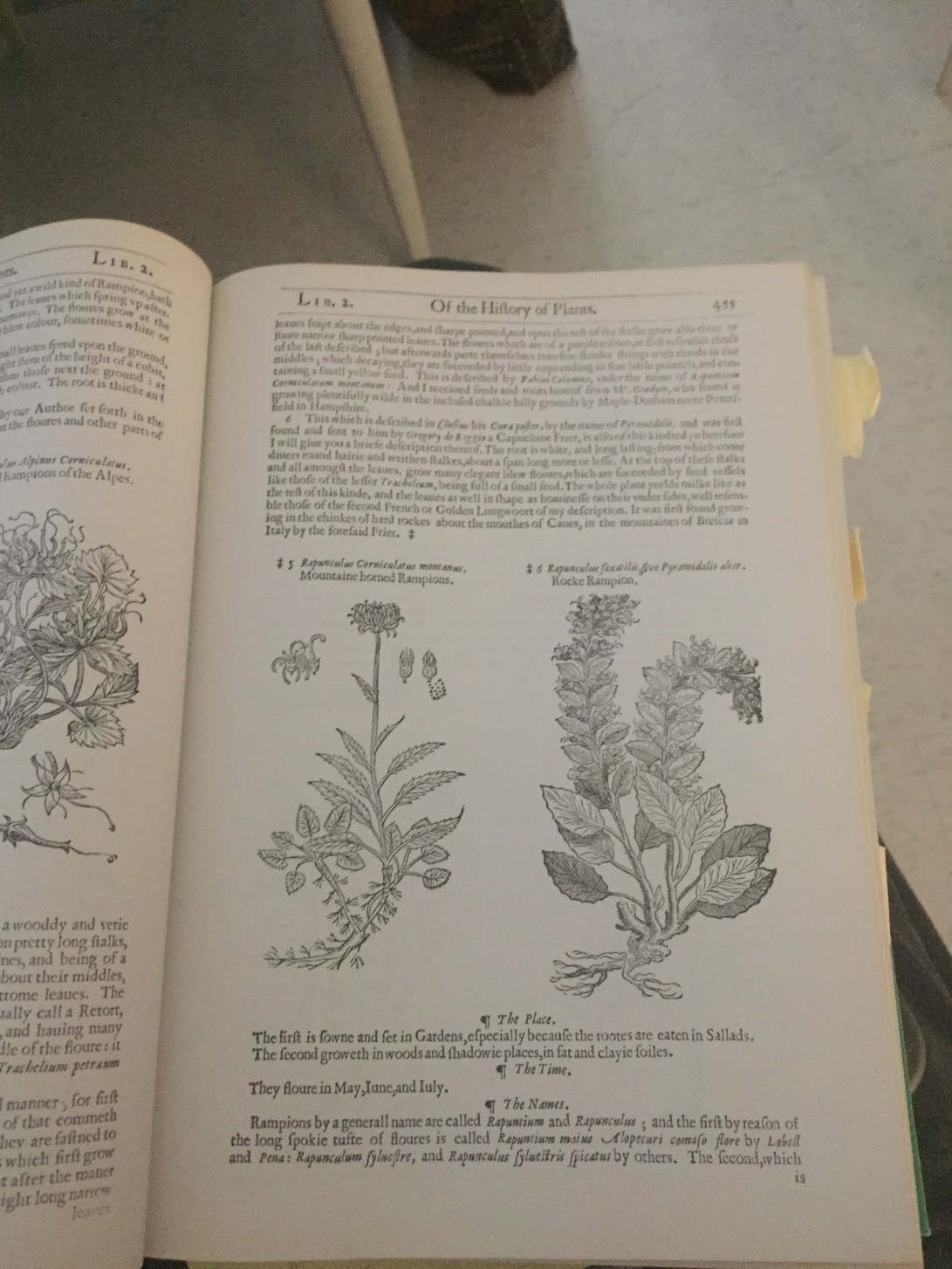

As a 17 year old in Barcelona, Joaquín took up the popular Art Nouveau style of the time. He made a living completing frescoes. These commissioned frescoes would be unrecognizable to the works of his eventual signature style. Soon, he was a well known teen artist in Spain. Eventually, he would move away from the Art Nouveau. Joaquín and other intellectuals of Barcelona formed the Noucentisme art movement. This new movement strove away from the embellished Art Nouveau. Joaquín would create, Lo Temporal No Es Mes Que Simbol, in this new bold style. The reception was mixed. While some lauded, others criticized as crude and flat. Among the conservative intellectuals, the biblical subject was thought as heretical for its unconventional depiction. This innovation and urge to be different would result in Joaquín’s upcoming signature style.

Lo Temporal no es més que símbol (Time is Nothing But Symbol), 1916.

As the artist and grew and matured, his works became more abstract. Joaquin would eventually hone down is signature style in 1929. Naming it himself, Univseralismo Constructivo (Constructive Universalism), Joaquín would incorporate his Uruguayan youth into his art. His work was enthused with a Pre-Columbian feel. The paintings were similar to indigenous South American art. This signature style would use flat and grid like formula. He restricted himself to the use an earthy palette. These earth tones would be found in all his works to come. In these grids he would add symbols, intending for a religious appeal. He wanted to give his art a spiritual and universal understanding. All of the symbols were arranged vertically and would include humans, crosses and words. This was called this his Cathedral Style.

“Composition”, 1931.

Joaquín would reach the height of his career and was obsessed with protecting his individualism. A perennial question of the avant-garde was, what is abstract? A question from the Circle et Carre (Circle and Square) group. Joaquín was determined on differentiating his Univseralismo Constructivo style from abstract art. Later in his career, Joaquin would add depth to these grids by adding shadows. As Joaquin grew old, he would travel back to South America and continue his art.

Construcción en blanco y negro (Construction in white and black), 1938.

Having visited an Arcadian art exhibit before, I had a preconceived idea of Arcadian Art. However, very few to the works in this exhibit resembled the other arcadian works. There were no bacchanalian subjects or another typical arcadian figures. Joaquín’s paintings are obscure and required analytical thinking to understand. His depiction of Arcadia was unfamiliar to me. It’s an Arcadia simplified to it’s basic philosophy of perfection. He achieves his utopia through his plain subjects and earthly palette. His art was likened to the Neo-Plasticist works of Piet Mondrian. This comparison can easily be seen. Joaquin’s arcadian perfection can be seen in the exacting segregation of color and line. The colors where pure and perfect.

Joaquin Torres-Garcia: The Arcadian Modern is a large exhibit encompassing art from his entire career. It was a mistake to label the exhibit Arcadian art. I really didn’t think arcadian philosophy was emphasized. Personally, Joaquin’s aesthetic did nothing for me. I thought the artworks we’re exciting and original. I wasn’t moved or effected in any way by the art. I respect what Joaquín had accomplished. He was an innovator that deserves his place in art history. For South America, a source of pride. What really made him unique was his incorporation of the non-western culture into his modern art. Joaquin deserves all the credit he has gained.

Joaquín Torres-García (Uruguayan, 1874-1949)

All source material taken from artwork descriptions.

Tyzer

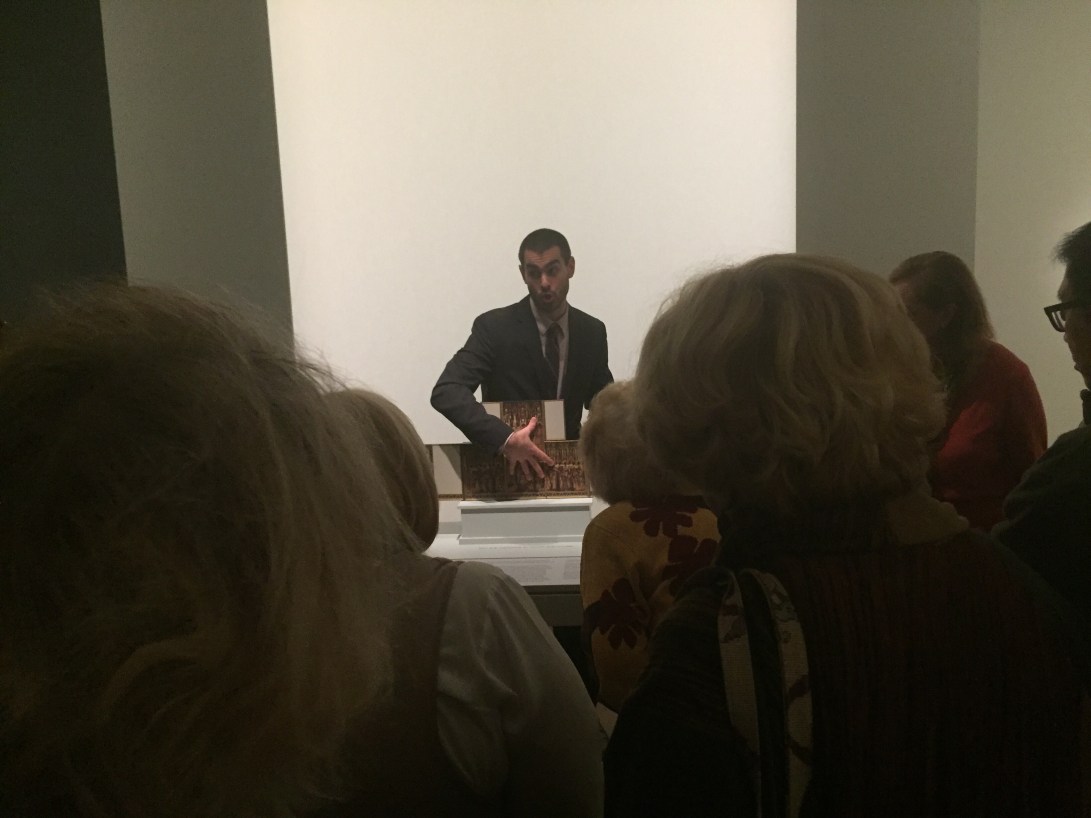

My thoughts on the exhibit, Audubon to Warhol: The Art of American Still Life – The Philadelphia Museum of Art, 12/29/15

This exhibit goes through the changes in American still life painting from just after The Revolutionary War until the mid 20th century. I thought the exhibit was well done. The subjects for the artworks were mostly of animals, objects and flowers. I feel that I gained a better understanding of the purpose and role of american still life painting as a whole and over time than I did on any particular still life artist. My favorite section of the exhibit was the art of the mid 19th century. The elaborate and idealized art displayed in this section really resonated with me. One thing that I found interesting was how many still life paintings Charles Willson Peale did. I had known him from his portraits of american presidents. He also named a lot of his children after famous artist including Rubens and Titian. A lot of Peale’s family painted still lifes and their works were also in the museum. One artist I felt was especially highlighted was William Michael Harnett. Harrnett’s work left a strong impression on me for it’s realness. The audio guide passage on Harnett was very good in describing the pub setting for his artwork. A lot of emphasis was put on Harnett’s work ‘After the Hunt’ (1883). In the mid 19th century they depicted still lifes in their nicest form instead of what was scientifically correct. It was a time of indulgence. In the late 19th century the art became more abstract. The role of still life’s switched more to the fast electric movement of the times. Georgia O’Keeffe was featured, as well as a mobile by Alexander Calder. In the final room I was completely shocked to see ‘Fountain’ (1917) by Marcel Duchamp. I had first learned about the piece from studying art history. I knew that this object is important to the Dada art movement and art history in general. These were my thoughts on the exhibit.

Pictured below from the exhibit is ‘Fountain’ by Marcel Duchamp, it was a reproduction from circa 1950.